Kicking down doors and wrestling pimps to the floor are a couple of movie-like moments people might imagine when thinking about a raid mission by Destiny Rescue. While our rescue agents have stormed houses with firearms, missions can best be described as careful and calculated and most lack this expected blockbuster appeal.

Our agents are also not alone but alongside their ally and near unsung hero, the police.

Barnett, one of our organisation’s rescue agents in the Philippines, says it is “vital” to join forces with law enforcement to execute raid rescue missions in the country.

“We really don’t want to do it without them,” he says.

The police carry a basket of resources, including helping prepare the mission, arrest traffickers, rescue girls and move them to safe homes, and create a stack of evidence against traffickers to lock them away for a long, long time.

We don’t want to run into these guys again. They’re criminal masterminds,”

What’s a raid mission?

A raid is a rescue mission where our rescue agents find victims of child sex trafficking and prepare an entrapment against their traffickers. Our agents, and police, often pretend to be customers and book a sexual service to meet the victims and traffickers at a location. Once together, our team reveals its identity, arrests the traffickers and rescues the victims.

325

RESCUES & 139 ARRESTS

Using this strategy, Destiny Rescue rescued 325 people and arrested 139 people across six countries last year.

Each mission changes in size, from rescuing 81 people to one person, but one commonality between them all is a collaboration with the boys in blue.

Due diligence

Peeking behind the curtains at a raid mission in the Philippines, Barnett and his team begin by spotting a victim of child sex trafficking and handing a pack of evidence to one of seven units under the National Bureau of Investigation, an agency of the Philippine government.

Pacts of evidence are “detailed” and can take days to weeks to complete, he says.

We prepare as much as we can,”

Unfortunately, there is no shortage of victims in the Philippines, a goldmine for traffickers, like many poverty-ridden countries. Up to 100,000 children are trafficked each year in the country, according to global anti-child exploitation network ECPAT International.

Rounding the troops

Once a unit gives our team a thumbs-up to prepare a raid mission together, Barnett can request support from a pool of about 20 other government bodies – though he needs only two of them to jump on board to complete the preparation of the mission.

On top of law enforcement, Barnett needs a local government official who has authority in a town or area where the mission is taking place. This person acts as a credible eye witness to the crime. But he warns there is a chance they could leak the mission to the target trafficker, causing the trafficker to “do a runner”.

“[Leaks result in] a lot of wasted time and resources, and the pimp is back out on the streets,” he says.

Assuming there is no leak, Barnett also needs the Department of Social Welfare and Development, a government agency tasked to protect the rights of Filipinos.

This agency provides a top resource. Barnett says after rescue, the agency gives victims support from social workers, a safe home, and coaching on how to speak against their trafficker and respond to lawyers in court.

Having all three agencies in a row creates a staggering amount of evidence against the trafficker when the case is presented in court after the raid mission.

It all adds to the charges against the suspect,” he says.

Life without badges

Without law enforcement and its collection of benefits, Barnett and his rescue agents would be left to perform a citizen’s arrest to capture a trafficker in the country.

Survivors also wouldn’t be coached on speaking at court, likely leading them to stay silent in court and the trafficker walking free. Plus, survivors would be left without the option of a safe home and could easily return to situations of exploitation.

“For the girls, nothing really changes,” he says.

The hours around a raid

Once rescue agents and their allies are ready, Barnett picks a venue to meet the trafficker and victims and execute the raid mission.

Teams gather for a brief prior to a raid. Before rolling out they stop to pray together.

When the traffickers and victims arrive at the venue, Barnett separates them, moving the victims outside in a huddle and the trafficker into a room. This segregation allows armed police to pounce and seize the trafficker without “traumatising” the victims, he says.

“That will scare the living daylights out of the girls. We’re pretty sensitive about that.”

After the police handcuff the trafficker and document the mission, Barnett signals for the social workers, alongside a dental and forensic team, to attend to the victims – now referred to as ‘survivors’. “There’s a few teams … It’s not just us and the cops,” he says.

Government and Destiny Rescue social workers reassure and assist girls during the raid. Towels are provided to protect girls’ identity in case media arrives.

Destiny Rescue social workers have been preparing for this moment since the raid was green-lighted. Anticipating the number and approximate ages of the survivors, they and their government counterparts enter with a calming confidence and help the girls through the next steps.

Called the “inquest stage”, Barnett says he now has 36 hours after the arrest to document each survivor. This includes interviewing them, inquiring about their birth certificates and allowing them to give a sworn statement – a written document reciting a first-hand witness of a crime.

We’re giving the girls a legal voice if they want to press charges.”

A day later, Barnett will request one of our drivers to transport the survivors to the safe home. While our team of social workers continues to walk with survivors during this transition, Barnett and his team will now eye their next child sex trafficking case and repeat the same process.

Pandemic’s toll

While raid missions play a major role in denting the number of children trapped in sex trafficking in the country, Covid-19 has been suffocating our team’s ability to complete missions.

Following the pandemic paralysing the world early last year, Barnett says many government agencies have been “severely understaffed”. This often means they don’t have the manpower to attend a raid mission at the drop of a hat, despite rescue agents finding evidence for a case.

“We’re meeting these girls and pimps and can’t do anything about it.”

Barnett says he and his team completed nearly 100 rescue missions in 2019 but completed only 40 missions last year.

Despite this decline, Destiny Rescue still rescued 142 people in the Philippines last year.

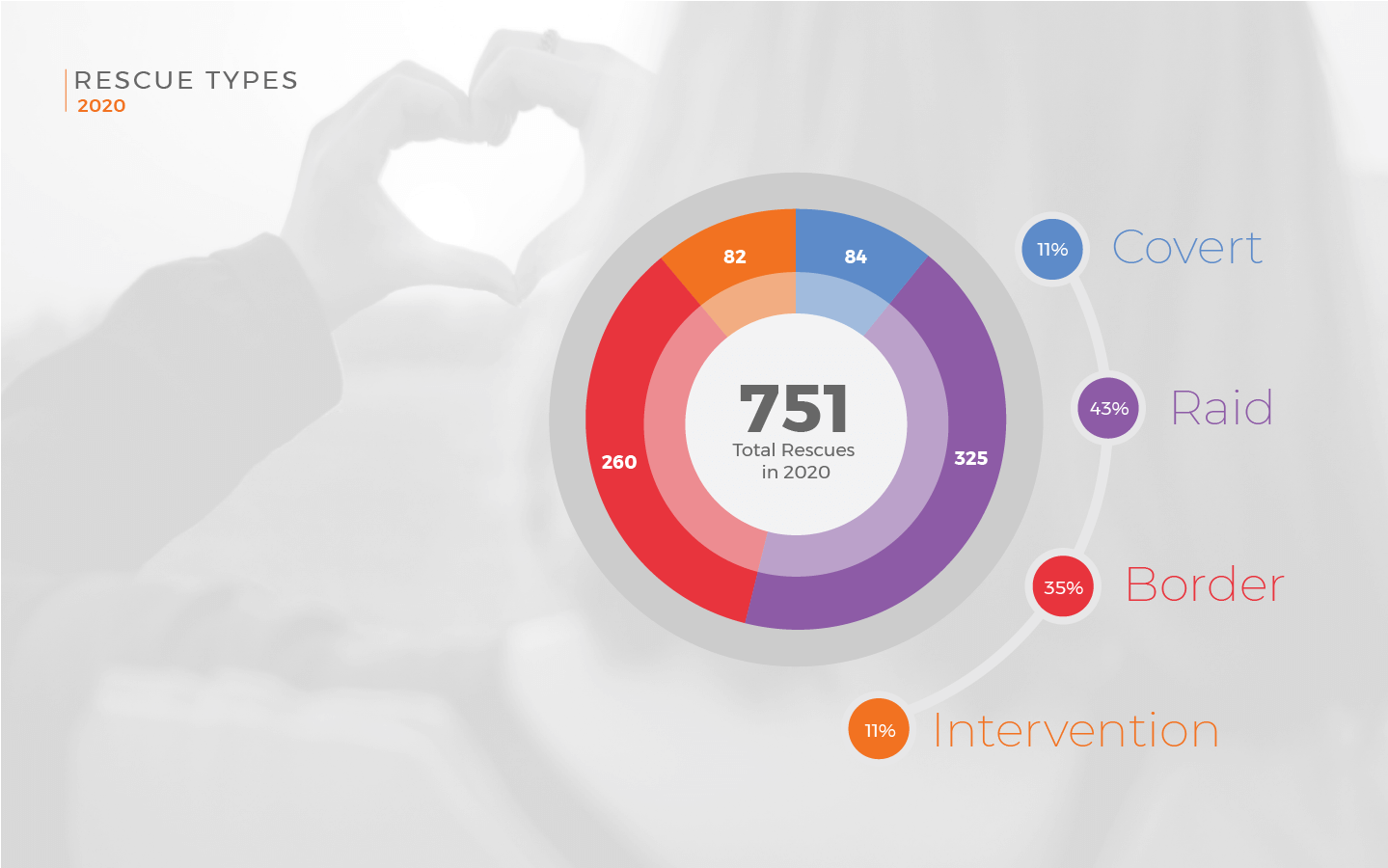

Across the Dominican Republic and six countries in Southeast Asia, including the Philippines, we rescued 751 people in total last year. Of this tally, 43% of them were rescued from a raid mission.

US & International

US & International New Zealand

New Zealand